https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-04-19/how-china-is-defending-its-detention-of-muslims-to-the-world

Peter MartinApril 19, 2019, 6:01 PM GMT+9 Updated on April 20, 2019, 4:27 PM GMT+9

At the Shu Le County Education Center, a sprawling three-story complex in China’s far west region of Xinjiang, the dormitories feature bars on windows and doors that only lock from the outside.

Inside are hundreds of minority Muslim Uighurs who have no way of leaving without an official escort, even though Chinese officials who took a group of foreign journalists around the “transformation through education” camp this week insisted they were there voluntarily. Asked what would happen if a Uighur refused to attend, Shu Le’s principal Mamat Ali became quiet.

“If they don’t want to come, they will have to go through judicial procedures,” Ali said after a pause, adding that many stay for at least seven months.

Shu Le is one of an unknown number of re-education camps in Xinjiang, a Muslim-majority region at the heart of President Xi Jinping’s Belt-and-Road Initiative to connect Asia with Europe. The U.S. State Department says as many as two million Uighurs are being held in the camps, a number disputed by Chinese officials even though they won’t disclose an official figure.

This week, I participated in a government-sponsored tour along with four other foreign media organizations through three cities in Xinjiang. The schedule was tightly controlled, with events planned from early morning to 11 p.m., and it included stops in many of the same places I visited on an unguided 10-day trip to the region in November.

Who Are the Uighurs and Why Is China Locking Them Up?: QuickTake

The trip shows that Beijing is becoming more worried about an international backlash that has intensified of late, raising risks for investors already assessing the impact of a more antagonistic U.S.-China relationship. Muslim-majority countries have begun joining the U.S. and European Union in condemning China’s practices, with Turkey’s foreign ministry in February calling the “concentration camps” a “great embarrassment for humanity.”

Xi’s policies to pacify the local population have spawned the biggest challenge to China’s international reputation since soldiers were sent to put down protests in Tiananmen Square three decades ago. After first denying the existence of the camps, China is now doubling down on the need for them, and beginning to defend them as a vital weapon against terrorism.

“You can see the Chinese government basically changed its position over time,” said Maya Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. “They switched from denial to a full-frontal counter offensive.”

Inside the Vast Police State Taking Over China’s Belt and Road

Throughout this visit, Chinese officials said the foreign media had given a false impression of the government’s efforts in Xinjiang. Most of the stops were focused on economic development and new education initiatives. The government’s message was simple: Xi’s policies were helping pacify the region and grow the economy.

The exercise reflects Xi’s increased confidence on the world stage, where he’s directly challenged Western-style democracy with a centralized model of government that uses advanced technology to reward, punish and ultimately control the behavior of its citizens. He has a lot at stake in making it work: Backing down risks jeopardizing the Communist Party’s grip on power.

I wasn’t able to speak independently with any residents on the trip, or travel around without being followed. But the group was allowed to ask questions of officials, including repeated follow ups that at times angered our hosts.

China Vows to Continue Crackdown Fueling Muslim Detention Camps

The visit to Urumqi, Kashgar and Hotan stood in stark contrast to the trip I took in November. Back then, minders followed close behind, searches occurred repeatedly and officials demanded I delete photos on my mobile phone. I could only glimpse the heavily secured camps from a distance.

This time around, government vehicles freely moved through various checkpoints, and metal detectors in public places were removed. Police officers who crowded city streets were gone. Still, my attempts to walk around unescorted were repeatedly unsuccessful.

After seeing the first camp, we were taken for a lamb lunch where women in colorful dresses danced to a song called “Happy Xinjiang.” An official ran after me as I walked away from the scene.

“I think you must be lost looking for the toilet,” he said. “Please let me show you.”

In Urumqi, we visited a graphic anti-terror exhibition featuring photos of decapitated and dismembered bodies. Later on at the main mosque in Kashgar, where a painting of Xi that earlier hung at the front had been removed, the imam said his father had been killed in a Uighur attack, leading him to “hate the terrorists.”

It’s Getting Harder to Report in China, Foreign Journalists Say

China’s crackdown on the region began after a series of Uighur strikes on civilians starting in 2013, including a flaming car attack in Tiananmen Square. The escalation alarmed authorities who had repeatedly attempted to pacify Xinjiang, most recently after 2009 riots in Urumqi killed some 200 people. Most of the dead were ethnic Han, who make up more than 90 percent of China’s population and the vast majority of the Communist Party’s leadership.

In Kashgar, I asked one guide if a single cadre in Xinjiang believed in Islam, which would be against rules in the officially atheist Communist Party.

“We haven’t discovered one yet,” said Wang Quibin, a local party leader in the city. “If we did, they would need to be punished severely.”

Once, he said, he asked a European official how their country controlled terrorism. “They said, ‘We take measures to control it as long as human rights are protected.’ I thought to myself, ‘Then how can you control it?’”

There’s no call to prayer anymore, he added, because everyone has watches. He said young Uighurs who grew beards were challenging local authorities in a similar way to anti-government protesters wearing yellow vests in France.

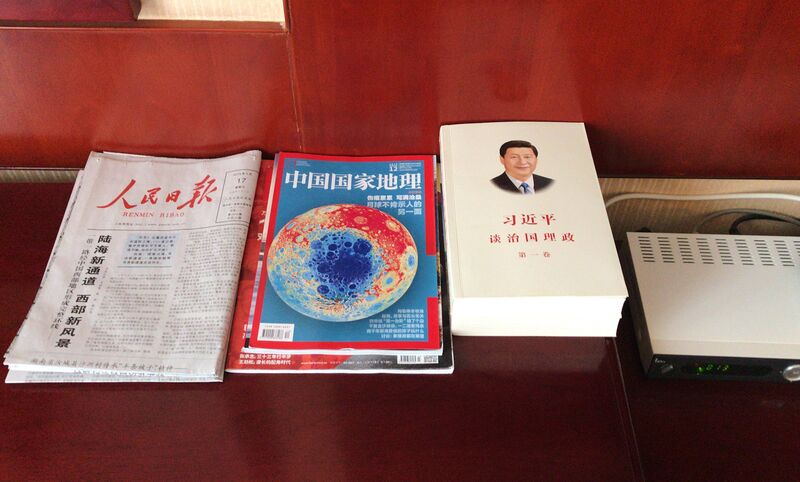

Another mosque in Hotan displayed copies of Xi’s book, “The Governance of China,” at the same level as the Koran. Hotels we stayed in featured brochures with Xi’s face along with his book.

“In our country there is no way to put religion above the law,” said Gu Yingsu, head of the propaganda department in Hotan.

‘Here Voluntarily’

China has sought to make the Xinjiang re-education camps palatable to the rest of the world. It removed watchtowers and razor wire from the Shu Le facility earlier this year, according to Shawn Zhang, a Chinese law student in Canada who analyzes satellite imagery of the camps in Xinjiang.

At a second re-education camp, the Moyu County Vocational Training Center in Hotan, Uighurs wearing ethnic clothes greeted us as we arrived. A staircase featured a large mural of the Great Wall and the words “China Dream.”

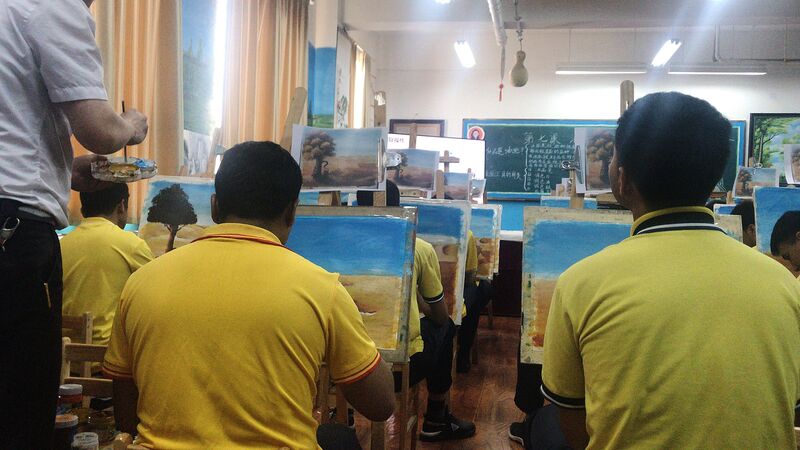

We observed a class in which men all painted the same landscape. Others learned practical skills such as Chinese massage techniques, and how to become waiters or nannies. There was even a class on botany.

We were allowed to speak to detainees only with minders present. None appeared to be physically harmed. Bloomberg isn’t identifying Uighurs in the camps, or using pictures of their faces, because it was unclear whether they were participating willingly in the events.

China Takes Diplomats, Media to Xinjiang ‘Re-Education Camps’

Each time we asked them what crimes they had committed, and each time we received similar answers with the same key phrases. They had been infected by “extremist thought” and sought to “infect” others before realizing the error of their ways in the camps. Many included the phrase: “I want to say that I am here voluntarily.”

Even more striking, the same detainees could repeat their answers word for word when asked.

I asked our minders why the answers were so similar. Gu, the official from Hotan, kept silent. One of her colleagues said the answers weren’t memorized. Xu Guixiang, deputy head of Xinjiang’s publicity department, said it was only natural they gave the same answers because they were asked about committing crimes.

“Perhaps it’s because they are nervous speaking to a foreigner,” he said. “It is difficult for them to express what they want to say in Chinese.”